StW-573 (Little Foot)

The StW-573 specimen has been the subject of a lot of attention and controversy. Parts of this skeleton were first identified by Ron Clarke in the 1990s when looking in boxes from previous excavations at Sterkfontein, a cave site in South Africa. Later Stephen Motsumi & Nkwane Molefe (seen in the image below) found the contact from where the bone fragment had been blasted off by lime miners well over 60 years previously.

As Clarke describes their work:

“Remarkably, after only a day and a half of searching, on the 3rd of July 1997 they found the contact from where the bone fragment had been blasted off by lime miners well over 60 years previously. The sectioned shaft of the right tibia and that of the left tibia alongside it were embedded in the concrete-like breccia of a steep ancient talus slope at the western end of the cavern (Fig. 3). This indicated the high probability that a whole skeleton was entombed within that breccia, hence my decision to excavate the area.”

After 20+ years of excavation and removing the skeleton from the surrounding matrix, StW-573, also known as Little Foot had its debut!

I mean, it is a pretty impressive-looking fossil. Here is a nice video talking about Little Foot:

"

Probably the part that has received the most attention is the age and the assignment to a species.

Cosmogenic isochron dating of the breccia in which the fossil was found places the fossil at ~ 3.67 Ma (around the same time as Australopithecus afarensis in East Africa). It is not clear how the individual was buried. The taphonomy of Sterkfontein is complex and much work has gone into figuring out the site formation processes. While Clarke admits it is speculative, he suggests a possibly scenario based on the fact that bones of a large baboon-like monkey were found intermingled with Little Foot and that fig trees tend to grow around entrance to dolomite caverns: Perhaps Little Foot and large male baboon got into a fight over resources from a tree and they fell into the shaft as a result. Again, it is hard to know for sure. Either way, it seems like they weren’t placed their intentionally (i.e. not a burial).

Clarke and Kuman assign StW-573 to the species Australopithecus prometheus, a speices rignally proposed by Raymond Dart, of Taung child fame. Not everyone accepts this designation. For a different take, check out John Hawks’ blog post.1

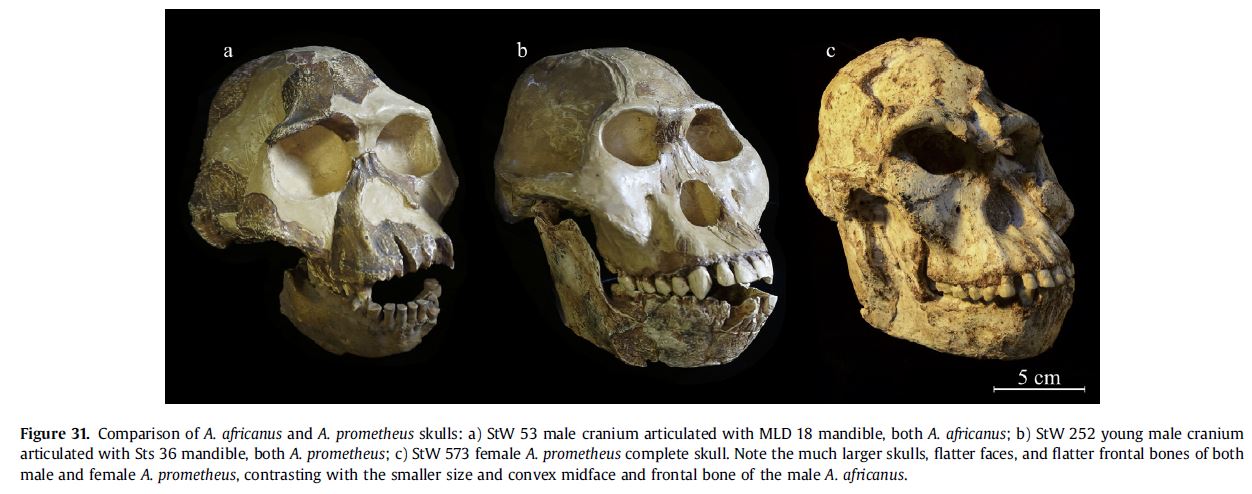

Ron Clarke has argued for awhile that there are 2 different species at Stekfontein: A. africanus and a second, more robust species with a larger, but flatter face. The image below (from Clarke and Kuman 2019 compares A. africanus (the first one) and A. prometheus (second and third). To be clear, the first two skulls have crania from one specimen articulated w/ the mandible of another one in order to show all the possible morphology. In general, Clarke and Kuman argue the A. prometheus have larger skulls, larger molars and canines, flatter faces, and flatter frontal bones than the A. africanus. Interestingly, the characteristics that they note lump A. prometheus together are similar to those of A. gahri from East Africa.

They suggest that the two species “overlapped temporally and geographically, perhaps even in a migratory pattern”

One theme that comes out of recent finds is the suggestion that there were multiple species of hominins living close in time and space. Of course, dating methods have wide error ranges and we are biased as to where we find fossils, but both this example and the MRD-VP-1/1 A. anamensis cranium suggest a species-richness that may have been underplayed in the past. Not everyone accepts this, though, so it should prove very interesting to follow these debates over the next few years…

if you are curious about naming conventions and current debates check out his and Berger’s paper and the response. In the interest of full disclosure I should note that John Hawks was my Ph.d adviser but I haven’t talked to him about this and am just going from the papers I read↩︎